California Roadkill Database Charts the Changing Wildlife Scene

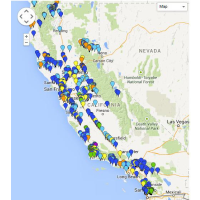

Roadkill map (map: California Roadkill Observation System)

Roadkill map (map: California Roadkill Observation System)

You can’t collect roadkill or eat it in California. That’s the law. But that doesn’t mean roadkill doesn’t have value.

Scientists at the University of California, Davis, have tracked 29,777 instances of roadkill on California roads over the past six years in an attempt to learn more about the animal movements and lessen the carnage. Volunteers file their reports online at the California Roadkill Observation System (CROS), which are entered into a database and mapped in an interactive graphic.

Zooming in on the map, one can make out patterns of different species slithering, storming and swooping across the roads at unfortunate moments in various locales. Around 350 of the state’s 680 vertebrates have shown up on the map at one time or another. The map is color coded to differentiate between birds, amphibians, reptiles and three sizes of mammals.

Contributors to the database are encouraged to upload photographs of roadkill, to provide context to the circumstances surrounding its demise. They respond enthusiastically. There are 367 pages containing thousands of such photos on the site.

Although the CROS website describes itself solely in terms of its commitment to reducing vehicle-wildlife collisions, its data has a broader application. Fraser Shilling, the UC professor running the database, told Vox, “Our system is the largest, most taxonomically broad wildlife monitoring system in the state.”

Changes in the frequency of a particular species landing in CROS can indicate changes in the ecosystem. Roadkill data, for instance, indicated that the invasive Eastern gray squirrel and Eastern fox squirrel were horning in on the habitat of the Western gray squirrel.

One potential use of the database is coordination with the network of wildlife corridors being nurtured statewide by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans). The Essential Habitat Connectivity Project is as much a strategy as an actual network, with its primary aim the provision of pathways for wildlife to move between habitats, like parks and wildlife reserves.

But if safety is an aspect of the network design—steering wildlife away from urban streets and industrial settings—it’s not showing up in the CROS database. Schilling told Vox, “There was really no difference between the areas inside and outside corridors, in terms of roadkill.”

The database may also provide yet another measure of the devastating drought, now in its fourth year. Schilling said he is working on a study that indicates there was a spike in the number of roadkill when the drought began. He speculated that there was increased migration as wildlife looked for water.

Recently, the trend has been toward fewer roadkill. That may be because there are fewer wildlife left to wander about.

–Ken Broder

Why Scientists Have Mapped 29,777 Instances of Roadkill Across California (by Joseph Stromberg, Vox)

California Roadkill Observation System (Crowdsourcing and Government)

What to Do When You See Roadkill? If You're in California, Report It. (by Année Tousseau, Sierra Club)

6 Things Scientists Have Learned From Studying Roadkill (by Joseph Stromberg, Vox)

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- California and the Nation

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- California Forbids U.S. Immigration Agents from Pretending to be Police

- California Lawmakers Urged to Strip “Self-Dealing” Tax Board of Its Duties

- Big Oil’s Grip on California

- Santa Cruz Police See Homeland Security Betrayal in Use of Gang Roundup as Cover for Immigration Raid

- Oil Companies Face Deadline to Stop Polluting California Groundwater