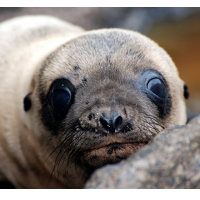

Inexplicably Sick Sea Lion Pups Wash Ashore for Third Straight Year

(photo: Misuzu Toyama)

(photo: Misuzu Toyama)

Scientists were groping for answers in 2013 when so many sick and starving sea lion pups washed ashore off the California Coast that the National Marine Fisheries Service declared it an Unusual Mortality Event (UME).

Many wrote it off as an anomaly because the California sea lion population had been steadily growing for years. There have only been 60 UMEs in the U.S. since 1991. But 2014 was pretty dismal, too.

And now the “unusual” has become the usual with another January of emaciated pups washing up on beaches from San Diego to the Bay Area. Older sea lions aren’t doing that well either.

“This is the third year that we’ve seen these mass die-offs, but this is the worst so far,” Shawn Johnson, director of veterinary medicine for the Marine Mammal Center, told the San Francisco Chronicle. “If this continues, there will be some long-term effects on the sea lion population.”

The Chronicle said 250 enfeebled pups, mostly around 7 months old, were rescued last month. A rehab facility in Sausalito that typically sees a dozen washed-up pups in January is treating about 108. Another 38 were reported under care in Laguna Beach. The center at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro registered 78 pups, which was said to be twice the number it saw in miserable 2013.

The babies, which are usually born in the summer and stay with their mothers until April, may have become separated when the adult ventured farther out to sea in search of food. But that is just speculation by scientists, who are baffled by why mother and child would separate before weaning is finished.

Investigations have failed to turn up any pathogens or toxins to pin the blame on. As is the case with any inexplicable ecological phenomenon these days, climate change, and accompanying warmer oceans, is a suspected influence. It’s possible that their food source has left or died.

Roger Thomas, president of the Golden Gate Fishermen's Association, suggested to the Santa Paula Press Democrat that maybe there are too many sea lions and nature is just taking its course. Thomas admitted to a bit of bias—“If sea lions are around, a salmon sports fisherman doesn't stand a chance. A sea lion will tear a fish right off the line and the angler is left with just a head.”—but there are a lot more sea lions around these days.

The sea lion population shriveled to 11,000 in the mid-1970s after Montrose Chemical Corps. manufactured and dumped thousands of tons of DDT for 20 years near the Channel Islands. That’s the main breeding ground for U.S. sea lions.

Scientists saw a connection (pdf). There was a scientific awareness of a problem in the 1960s; the company stopped dumping DDT in 1970; and a couple years later Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

That helped. By 1993, there were 22,000 sea lions. The population grew to 60,000 in 2009 and an estimated 300,000 today. It’s hard to say how many sea lions there were before commercial interests killed them for their blubber (oil), hides and genitals in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But a fair guess would be more than 300,000.

–Ken Broder

Sea Lion Strandings Approach Record Level in California (by Kurtis Alexander, San Francisco Chronicle)

Mystery Malady Affecting Sea Lion Pups Strains Sausalito Wildlife Center (by Mary Callahan, Santa Rosa Press Democrat)

Sick Sea Lions Wash Ashore in California; Rescuers Brace for Bad Year (by Amy Hubbard, Los Angeles Times)

Something Inexplicably Awful Is Happening to California Sea Lion Pups (by Ken Broder, AllGov California)

Californian Sea Lion (Seal Conservation Society)

DDT in California Sea Lions: A Follow-Up Study After 20 Years (University of California, Santa Cruz) (pdf)

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- California and the Nation

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- California Forbids U.S. Immigration Agents from Pretending to be Police

- California Lawmakers Urged to Strip “Self-Dealing” Tax Board of Its Duties

- Big Oil’s Grip on California

- Santa Cruz Police See Homeland Security Betrayal in Use of Gang Roundup as Cover for Immigration Raid

- Oil Companies Face Deadline to Stop Polluting California Groundwater